Society

Did the Selfie Self-Combust?

Post-pandemic, photo uploads of yourself are the epitome of gaucheness. Hattie Crisell on how COVID-19 killed off selfie culture and what’s emerging in its vainglorious wake.

by : Hattie Crisell- Mar 29th, 2021

GABRIELLE LACASSE

It was a well-meaning gesture. When a fresh-faced Gal Gadot gazed into her phone and started a celebrity singalong of John Lennon’s “Imagine,” she was trying to cheer up the masses during lockdown—but the backlash was fast and fierce.

“If there’s a textbook definition of the expression ‘out of touch,’ this is it,” declared one commenter on Instagram. In the past, celebrities had been applauded for that kind of thing; just look at the rapturous reception that the likes of will.i.am and Scarlett Johansson got for their 2008 Obama-campaign-supporting “Yes We Can” video. But 2020 was different—because it was the year that we finally lost our patience with the cult of me, me, me.

This moment marks the end of an era—one of flagrant self-obsession. Thus far in the 21st century, we’ve succumbed wholeheartedly: Our dominant media is now social media, and while at first we talked about it in terms of “networking,” we quickly forgot that and began to speak of “branding” instead. It’s now every individual’s task to carve out a carefully curated image of themselves—or who they’d like to be—and send it out worldwide. “We have data showing that narcissistic people have more Facebook friends and more Twitter followers,” says W. Keith Campbell, psychologist and author of The New Science of Narcissism. “Social media is a breeding ground for narcissism.” Even in 2006, four years before the launch of Instagram, Time bestowed its Person of the Year honour on “You”—a celebration of all those who were uploading their lives to the internet.

This is the century in which “selfie” has been added to the dictionary and in which personal blogs have given way to YouTube channels, Instagram grids and TikTok accounts that document our every move. Self-help has thrived, boosted by a wellness industry that champions self-care and self-diagnosis. Any fool (including the one who is writing this article) can put out a podcast or self-publish a book.

In 2018, solipsism peaked when designers Tommy Honton and Tair Mamedov created the Museum of Selfies in Hollywood and packed it with imaginative backdrops that make for great social-media content. It was inspired by a flurry of visitor attractions around the world, including museums of ice cream, candy and optical illusions, that were already doing the same thing—they just weren’t advertising it as such. “I thought it was funny how these experiential companies would bend over backwards trying to make it seem like they were anything other than selfie palaces,” recalls Honton.

It’s no coincidence that one of the foremost celebrities of our age is billionaire Kim Kardashian; she has so completely captured the zeitgeist that it has felt like we’re living in her dream. In 2015, she released a shiny book of selfies. Its title: Selfish.

So when, and how, did the wind change? We had become so comfortable in the age of self-obsession, with its applause for all things confessional and self-celebrating, that it seemed we would live like that forever. But it was Kardashian who gave us the first clue that unabashed ego was no longer okay. Three years after Selfish came out, she told an interviewer, “I don’t take selfies anymore; I don’t really like them anymore.” Soon after, it emerged that she was training to be a lawyer and had shifted her attention toward campaigning for prison reform. Then she announced the end of her reality show, Keeping Up With the Kardashians—which, in a way, was a 13-year selfie.

If our queen of social media felt the shift first, the rest of us followed—especially once we were hit by a global pandemic. First, there was a backlash to Ellen DeGeneres complaining of lockdown boredom in her mansion, Jennifer Lopez sharing videos of her sprawling Miami garden and Madonna in her bath declaring COVID-19 to be “the great equalizer.” These self-indulgent celebrity posts couldn’t have felt more tone-deaf in March and April 2020 amid rising death rates and plummeting employment.

And our tolerance of shameless narcissism only lessened from there. When George Floyd was killed by police in May, igniting months of Black Lives Matter protests, Instagram became a place for declarations of anti-racism; even the most politically oblivious knew that it wasn’t the time for oiled-up workout selfies or shots of designer shoes. When a Russian influencer was seen staging a photo shoot at a protest, she was shamed online by fashion watchdog @diet_prada.

Then, in July, “Challenge Accepted” swept the internet, morphing into an abhorrent display of mass ego-stroking. The original idea was for women to highlight skyrocketing rates of femicide in Turkey by posting defiant black-and-white pictures of themselves, but it didn’t take long for this message to be lost and for Instagram to be awash with flattering selfies. They included confused posts by celebrities such as Jennifer Aniston (“Truth be told, I don’t really understand this #challengeaccepted thing”) and Reese Witherspoon (“This is what sisterhood is all about”) featuring incredibly flattering images of themselves.

As a result, the project descended into ridicule. “It isn’t just a game of hot or not,” pointed out behavioural scientist Pragya Agarwal. “Or an exercise in vanity…. It is a very serious gesture of defiance in support of Turkish women.”

But in the midst of a knotty time on social media, something unexpected emerged. It was shared and shared until Instagram took on a new flavour: Enter the infographic influencer, who posts slide shows with titles like “Cultural Appropriation or Appreciation?” (@emmadabiri), “Veganism & White Privilege” (@venetialamanna) and “Sitting With Discomfort” (@mixedwomxn). These users share not outfit inspiration but difficult ideas and educational tools, wielding influence on things that matter. Newly awake to a world beyond ourselves, we clicked “follow” by the thousands.

“Now, more than ever, people want to feel, see and be part of the action—so they’re looking to those they follow to be active on important causes,” explains Georgia Kelly, strategic partner manager at Instagram. “During lockdown, communities rallied for worthy causes; in the wake of Black Lives Matter, people from all backgrounds united in a desire to make change happen. Now there are more than a million followers of #blacklivesmatter, and since July, the hashtag has been used over 56,000 times daily on average.”

All of this contributes to a rather more earnest mood online. Pandora Sykes, who writes about social media and authenticity in her book, How Do We Know We’re Doing It Right?, frequently shared images of herself when she worked in the fashion industry but posts far fewer nowadays—although she still speaks up in defence of the selfie. “Do you define it as narcissism or do you interpret it as the search for self-knowledge, self-actualization and self-expression?” she asks. “We’ve always been looking to say ‘This is who I am.’ I think what we’re seeing is the centring of political and social movements, but [these movements are] still hinged on the self—because that’s the most effective way to communicate on a visual platform.” Sykes cites Florence Given, the artist and bestselling author of Women Don’t Owe You Pretty, as an example. “She posts very cool pictures of herself, and most of her activism is done through her own image.”

Given shares a combination of placard-like slogans (“White people, we have work to do”) and self-portraits that use her face and body as symbols of defiance. She often sits with her legs splayed wide, a power pose that seems to challenge “manspread- ing”; she is glamorous and unapologetic. Her photos are fiercely self-expressive yet seem to be modelling a strength that we might all be able to share.

This new breed of influencer has definitely changed the look of our Instagram feeds, but the question is: How deep does that change go in our culture? Have we really given up on self-obsession? Experts on the phenomenon aren’t convinced. “The selfie appears to be in decline but only because culture has moved on and people have found a new way of signalling status,” says Will Storr, author of Selfie and the forthcoming book The Status Game. “We don’t broadcast our membership in elite groups with our faces anymore—we do it with our beliefs. It seems to me that people on social media are every bit as narcissistic today as they were during the Kardashian heyday. The self-obsession is still there, but it manifests in a different form.”

Campbell echoes Storr’s view, though he says that it’s too soon to call. “I don’t know how much of the new activism is reflected narcissism and attention-seeking,” he says. Genuinely caring about a social movement doesn’t mean we’re not also hoping to attract 1,000 likes and be congratulated on our immaculate beliefs. “We do know from research that people who are narcissistic engage more politically—they want their ideas out there; [they want] to change people. So what looks like social justice may be serving the ego as well.”

Nowadays, we may not pout into our phones as much as we used to; we might think twice before showing off the dress we were #gifted or the breakfast we’ve eaten. Instead, we might caption our own image with words about inequality, share the inspiring books we’re reading or tell our followers about our mental health, hoping we can change the world. It’s a dollop of doing good but often with a sprinkling of looking great. This, in 2021, might be the new me, me, me.

Read more:

84 Coronavirus Quotes That Show Human Beings Will Always Find The Funny Side, Even in a Crisis

Sandra Oh Delivers Powerful Speech at Stop Asian Hate Rally: “I’m Proud to Be Asian”

Ethical AI Has Not Solved Tech’s Problem with Racism

Newsletter

Join our mailing list for the latest and biggest in fashion trends, beauty, culture and celebrity.

Read Next

Fashion

Zendaya Welcomes Spring in a Retro Floral and Tulle Dress

Another day, another preppy tennis-core look.

by : Briannah Rivera- Apr 23rd, 2024

Culture

A Joe Alwyn Source Explains Why He Didn’t Want to Talk About Dating Taylor Swift

Following the release of The Tortured Poets Department, new insight about the British actor’s decision emerges.

by : Alyssa Bailey- Apr 23rd, 2024

Culture

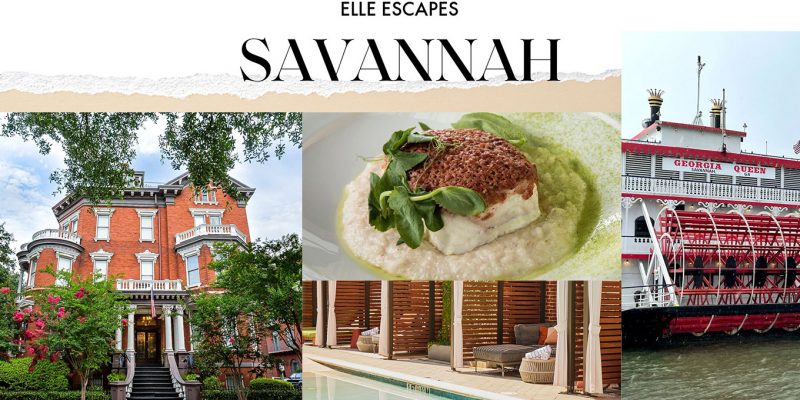

ELLE Escapes: Savannah

Where to go, stay, eat and drink in “the Hostess City of the South.”

by : ELLE- Apr 15th, 2024