Society

Birth Alerts

The government practice of separating women from their newborns is steeped in discrimination and systemic racism, especially toward Indigenous peoples. It’s time we challenge these actions, which have done so much more harm than good.

by : Camille Cardin-Goyer- Aug 16th, 2021

Meky Ottawa

Miigwan* is almost two weeks overdue, but her small bump and slender frame make it less noticeable. The pregnancy—her fifth—has been fairly uneventful, but she’s withdrawn and troubled, as if a dark cloud has hung over her for the past 42 weeks. She considered getting an abortion several times but ultimately decided to carry to term. The thought of holding her baby for the first time is enough to overcome the fear that it will be taken away minutes after being born and placed in foster care, like her four other children—none of whom she has seen or spoken to in years. Terrified of facing racial discrimination in the health-care system—which took the life of Joyce Echaquan (a 37-year-old Atikamekw mother of seven who filmed herself being insulted and mocked by hospital staff not long before she died, last September, in Joliette, Que.) and countless others—she avoided accessing prenatal care, even though the Val-d’Or hospital is just a 30-minute drive from the reserve where she lives. Now that she’s in labour, she can no longer avoid it and goes to the hospital to give birth. For the First Nations women in Miigwan’s Anishinaabe community of Lac Simon, Que., that 30-minute drive is nerve-racking because they know what awaits them upon arrival.

The tears Miigwan sheds during delivery are not happy ones—they’re tears of despair. A birth alert has been issued. This is the controversial practice of notifying child-welfare workers about a newborn believed to be at risk of harm; it’s done without the parents’ knowledge and often results in the baby’s apprehension (removal from the care of its mother). Indigenous parents are subjected to these alerts at a far higher rate, and for the fifth time, Miigwan has been flagged.

Expecting a social worker to arrive any minute, she holds her daughter tight, skin to skin, memorizing her gentle touch, feeling her rapid heartbeat slow to meet hers and staring into her big brown eyes. Miigwan’s daughter is about to become one of the almost 15,000 Indigenous children in Canada’s foster-care system. And despite Indigenous children accounting for only 8 percent of the country’s youth, 52 percent of children under the age of 15 in foster care are Indigenous.

A closer look at Canada’s foster-care population shows that not only are Indigenous children disproportionately affected but their overrepresentation in the system continues to grow each year, to the point where there are three times as many First Nations children in state care today as there were at the height of residential-school apprehensions. This can be attributed to a number of issues, most of which stem directly from colonialism and ensuing discriminatory child-welfare practices.

Canadian child-welfare services fall under the jurisdiction of provincial and territorial authorities, and although each province has different legislation regarding its interventions, the situation is alarming from coast to coast. In Quebec, the number of Indigenous children who are placed in foster care is eight times that of non-Indigenous children, and one region in particular stands out for its shockingly high number of birth alerts: Abitibi-Témiscamingue, which is home to seven Algonquin communities.

For years now, Lucien Wabanonik, band councillor for the Anishinaabe Nation of Lac Simon, has been voicing the communities’ concerns and fears and working toward improving communication with the provincial government. “They won’t listen,” he says. “The voices of our people are disregarded, and, meanwhile, pregnant women prefer risking the six-hour drive to Montreal rather than giving birth right here in Val-d’Or, where they know there’s a good chance their child will be apprehended.”

Canada’s present-day child-welfare approach to Indigenous youth goes back to government policies that were created to assimilate Indigenous peoples, and it’s easy to draw parallels between the displacement of Indigenous children through forced residential schooling (from 1876 to 1996), the Sixties Scoop (from the mid-’50s to well into the ’80s) and today’s birth alerts. “It’s appalling that after all those years, 2021 is when Indigenous kids in care have reached an all-time high,” says Wabanonik. “This proves that government attitudes toward Indigenous peoples have not changed one bit; systemic discrimination is embedded in the fabric of this country, and it is even apparent in the hospital care (or absence thereof ) we’re getting.”

In February 2020, the University of Toronto published a literature scan on the efficacy of birth alerts in ensuring the safety of children. Findings revealed that evidence-based research assessing their effectiveness is limited; meanwhile, it’s well known that the foster-care system has negative lifelong impacts on the health and well-being of children (who experience things like severe attachment and bonding issues) and families (among whom depression, anxiety, stress, pain and grief are common), particularly those in marginalized populations such as the Indigenous peoples of Canada. Coroner Eric Lepine has dealt with a number of cases of death by suicide in Nunavik, many of whom were Inuit teenagers, and more often than not his investigations highlighted great inconsistencies in the youth-protection services provided for Indigenous children. “I noticed a pattern of systemic issues affecting youth-protection interventions, such as a lack of personnel, high staff turnover and growing distrust,” he says. Only a few provinces have not yet banned birth alerts, but the practice is at least under review in all except one: Quebec.

“Only a few provinces have not yet banned birth alerts, but the practice is at least under review in all except one: Quebec”

In Miigwan’s community, some women are actually threatened by their assigned social worker. “They’ll literally say ‘You know I’m going to take your child, right?’” says Wabanonik. “Countless [women] have come to me asking whether they should get an abortion, because even if they follow through with their worker’s recommendations, they likely won’t get to keep their child in the end. This cycle must be broken.”

A lot of the mothers who were once in youth protection now have children in youth protection, so “cycle” is a fitting term. “The Indigenous women who enter the youth-protection system [to try to get their children back] are ill-equipped to navigate it,” says Nakuset, the executive director of the Native Women’s Shelter of Montreal. “It’s trauma on top of trauma.” Born into a Cree community in Lac La Ronge, Sask., Nakuset was adopted by a Jewish family in Montreal as part of the Sixties Scoop. “I’ve been working here since 1999, and usually if you have a child in youth protection, they’ll automatically take the next one—they literally wait at the hospital to take that newborn,” she says. “I started noticing this trend 20 years ago. And it’s the children who suffer. It’s the mothers who suffer. It’s the people who drink themselves to death because they’re so heartbroken who suffer and the children who grow out of the system only to have their children taken away.”

Nakuset and her staff have become advocates. They go above and beyond to try to curb this practice, but they’re not getting anywhere. Even if these mothers prove to youth protection that they followed the recommendations, they won’t get their children back most of the time and are still flagged in the system. “We had a woman who was under the impression that she was going to get her child back, and my staff went to the youth-protection court hearing,” says Nakuset. “The social worker had written on her file ‘This woman is a risk to her child because she is Inuk,’ so they walked up to the judge and said, ‘This is discrimination!’ I challenged youth protection following the incident, but they never gave me a clear answer as to why that was [written] there and why nobody had looked into this.”

The Native Women’s Shelter of Montreal has initiated several collaboration agreements with Quebec youth protection in order to push for prevention services that are informed by the experiences of Indigenous families, but none of these services have been put in place. “We have to create our own services because we’re not getting anywhere, and what’s worse is that youth protection won’t even talk to us anymore,” says Nakuset. “We have to send our staff to the hospital when women give birth so they can fight off social workers.”

“We have to send our staff to the hospital when women give birth so they can fight off social workers.”

The first call to action outlined by the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) referenced the child-welfare system and the urgent need for federal, provincial and territorial governments to reduce the number of Indigenous children in care by ensuring that social workers are properly educated about the history and impacts of residential schools so they can provide more appropriate solutions for family healing. Four years later, Quebec’s Viens Commission—a provincial inquiry—determined that the Youth Protection Act needed to be amended because it is incompatible with Indigenous traditions and culture. It also recommended that youth-protection evaluations and decisions take into account historical, social and cultural factors related to First Nations and Inuit and that the discriminatory clinical evaluation tools used by youth protection be overhauled.

When the Viens Commission report came out, Quebec premier François Legault—who still refuses to acknowledge that systemic racism exists in the province—said it was clear that previous provincial governments had to bear responsibility for the poor treatment of First Nations people and Inuit. “Years ago, I asked youth protection if the TRC was a priority for them,” says Nakuset. “‘Not even on our radar’ was basically their answer.” The year before the Viens Commission recommendations came out, Nakuset and her team met with Linda See, the director of youth protection for Batshaw (the English component of Quebec youth protection), and asked if together they could try to anticipate some of the calls to action so that youth protection would be ahead of the game when the report came out. “They wouldn’t allow it,” says Nakuset. “And none of the Viens Commission’s calls to action have been applied since, so we just keep showing up. We’re knocking at their door, saying ‘We can provide services using our own resources—social workers, addiction workers, psychologists, art therapists, elders, you name it. We can train your staff. We can help.’ But they don’t want the help.”

On January 1, 2020, federal Bill C-92—a legislation allowing Indigenous groups to finally take over their own child-welfare systems and prioritize the placement of Indigenous children with members of their extended families and communities— came into effect. But celebrations were cut short when, citing a threat to provincial jurisdiction, the Legault government immediately asked Quebec’s Court of Appeal to rule on the constitutionality of the law.

“We weren’t all that surprised,” says Richard Gray, social services manager of the First Nations of Quebec and Labrador Health and Social Services Commission. “The Legault government won’t let go of its control over us. It’s a major lack of recognition of our self-governance and self-determination—it’s a sad message they’re sending to First Nations.” Adopted by the UN in 2007, the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples—which Legault won’t endorse—recognizes Indigenous peoples’ right to self-determination and reaffirms that in the exercise of their rights, they should be free of discrimination of any kind.

In April 2021, another report—the Special Commission on the Rights of the Child and Youth Protection—highlighted once again the child-welfare system’s inability to adapt to Indigenous realities and urged the provincial government to favour self-determination and push for prevention services. “Can Indigenous communities take charge of their own youth protection?” asks Lepine. “Yes. What are Legault’s reservations? I don’t know, but it probably has to do with centralization and control. It’s unfortunate.” The Quebec Ministry of Health and Social Services did not respond to requests for comment on the province’s plan to enact the latest commission recommendations.

In the wake of C-92—and until Quebec’s Court of Appeal rules on the constitutionality of the law—some Indigenous communities in the province have managed to create their own youth-protection agencies. Mino Obigiwasin, a project Wabanonik helped launch in collaboration with the region’s government-run Integrated Health and Social Services Centre, now services four Anishinaabe communities in Abitibi-Témiscamingue. “When a child is flagged by youth protection, a First Nations officer handles the placement of the child, either with extended family, neighbours within the community or an Anishinaabe family in a neighbouring community—anything to prevent the child from being placed in a non-Indigenous family,” he explains. So far, the initiative is showing favourable results. “There’s a much greater understanding of and respect for our culture and values,” he adds. “We believe that the approach to family and child welfare should be more human. There’s no recrimination in our approach; it’s more supportive and comprehensive of the child’s and parents’ needs. In most cases, the solution to a child’s well-being doesn’t lie in cutting out the parents.”

The court hearings for the appeal of C-92 are scheduled for September 13 in Montreal. “We’re really hoping that Quebec changes its attitude toward birth alerts,” says Gray. “Will they ban the practice altogether? Will they work out new protocols with First Nations to start supporting young mothers and their children? Things have to change. Collaboration and co-operation is all we’re asking for.”

Newsletter

Join our mailing list for the latest and biggest in fashion trends, beauty, culture and celebrity.

Read Next

Fashion

H&M's Latest Designer Collab With Rokh Just Dropped (And It's So Good)

We chatted with the emerging designer about the collaboration, his favourite pieces and more.

by : Melissa Fejtek- Apr 18th, 2024

Culture

5 Toronto Restaurants to Celebrate Mother’s Day

Treat your mom right with a meal at any of these amazing restaurants.

by : Rebecca Gao- Apr 18th, 2024

Culture

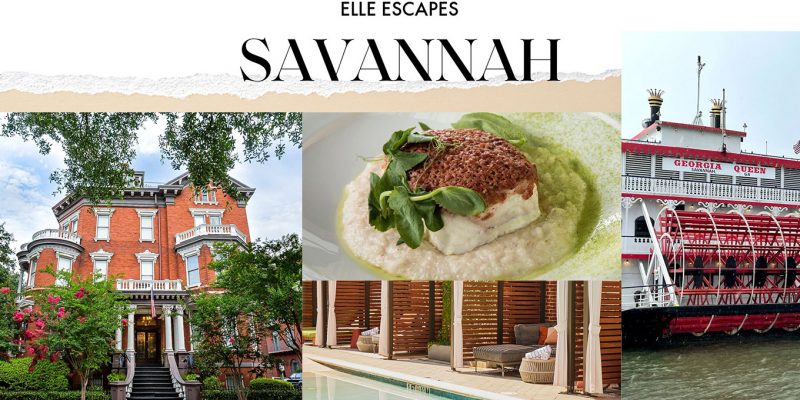

ELLE Escapes: Savannah

Where to go, stay, eat and drink in “the Hostess City of the South.”

by : ELLE- Apr 15th, 2024