Music

A New Queer Line-Dancing Movement Is Heel Tapping Its Way Into Canadian Nightlife

Get in line.

by : Joanna Fox- Dec 29th, 2023

CLAIRE PRESTON

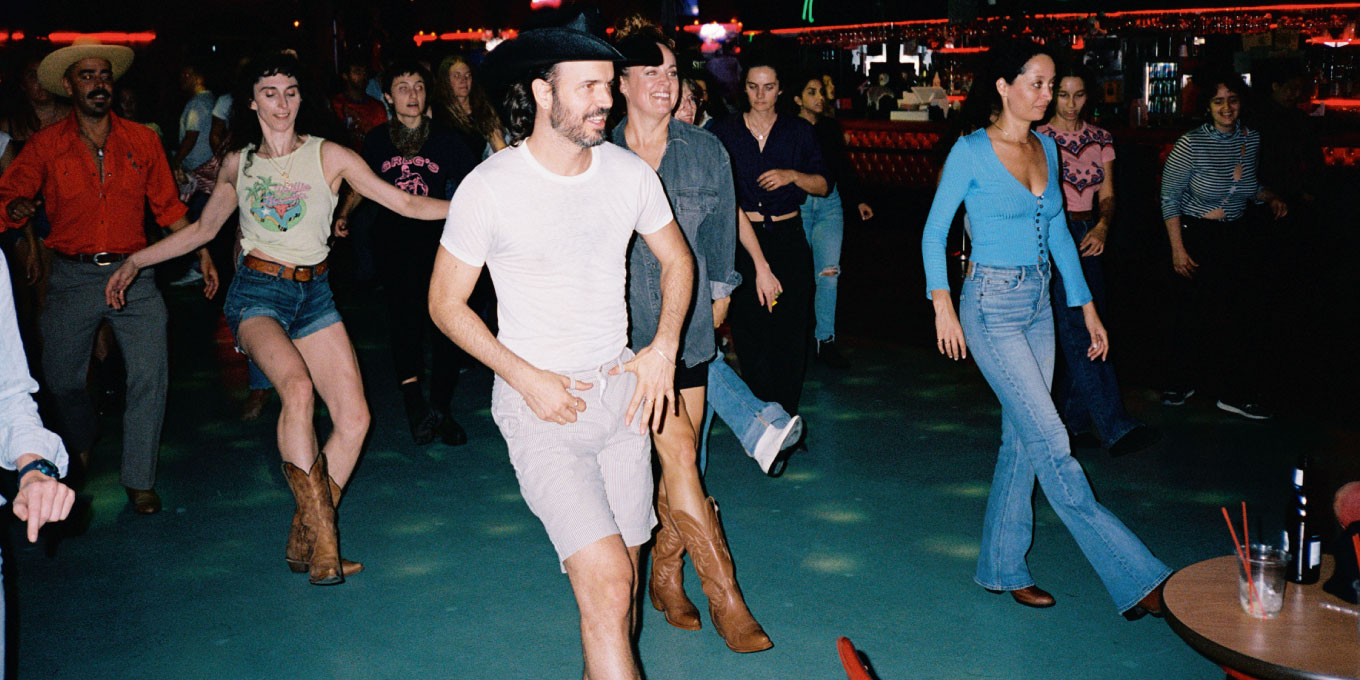

It’s 8 pm on a Monday night at the end of August—one of those perfect warm late-summer Montreal evenings when the moon is plump and low-hanging and everyone seems to be out, eating and drinking on terraces and spilling out onto the streets. The last thing anyone would want to do is be in an upstairs enclosed space. But I make my way up the time-worn wooden staircase that leads to Champs, a queer-friendly sports bar on Saint Laurent Boulevard, and find that the room is packed with people ready for Spurs, the bar’s new line-dancing night. Some patrons are sporting cowboy boots and denim vests, some are in tasselled shirts, but most, like me, are simply in jeans and a tank top. It’s already hot in here, and we haven’t even begun dancing yet.

Our host for the evening, filmmaker Pat Kiely, stands on a platform at the front of the room holding a microphone and wearing worn-in black leather boots, white jeans and a short-sleeved collared shirt that has a whisper of Western vibes. He announces that he’s going to be leading us solo because his teaching partner, Canadian actor Kathleen Munroe, has a new gig in Toronto (everyone cheers in support), and then he reminds the crowd of the golden rule: “No drinks on the dance floor!” Shania Twain’s “Any Man of Mine” starts playing, Kiely calls out the moves and everyone breaks into a routine that’s “relatively simple,” accord- ing to the regulars, who are stepping, kicking, heel tapping and clapping to my left and right. After all, we’re just getting warmed up.

This is not the first time I’ve been invited to line dance over the past few months. When I was visiting Los Angeles, former Montrealer (and an old colleague of mine) Pierluc Dallaire wanted me to experience Stud Country, a queer line-dancing night at Club Bahia in the city’s Echo Park borough. It was founded by Sean Monaghan and Bailey Salisbury in 2021 after Oil Can Harry’s—the oldest gay club in L.A.—sadly closed after 52 years of business. It was well known for its Friday line-dancing night and was a key safe space for the LGBTQIA2S+ community. Monaghan and Salisbury had been dancing there since 2017, so when it shuttered, they decided to find a new home for the night they cherished so much.

Dallaire, who is the director of operations at Botanica, a restaurant in the L.A. neighbourhood of Silver Lake, had been taking recreational dance classes pre-pandemic and felt very isolated during the lockdown months. “Everything was still closed, and we were doing a [dance] class in the park, and it kind of sucked,” recalls Dallaire. “One of my friends was like, ‘Hey, you should go see Bailey and Sean; they’re doing this night called “Stud Country.”’ We were only about 20 people in this weird space with our masks on in the middle of summer, and it was really hot, but it was so much fun. Then it just kind of became a community with a really cool, inclusive space to hang out, have fun and meet friends—and just line dance.”

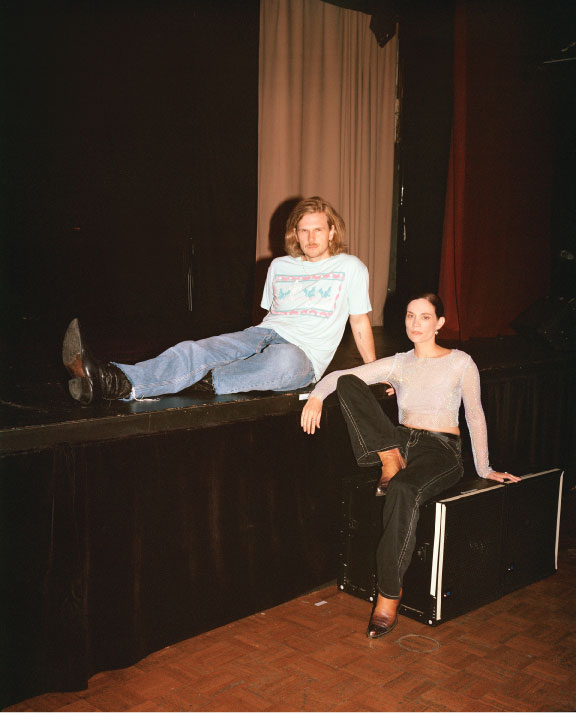

PAT KIELY AND KATHLEEN MUNROE

BRITTANY CARMICHAEL

BRITTANY CARMICHAELKiely and Munroe, who are from Montreal and Toronto respectively, also became regulars at Stud Country while living in L.A. and fell in love with not only the dancing but also how it made them feel like they were part of something special. Kiely was dancing at well-known choreographer Ryan Heffington’s former studio, The Sweat Spot, when he heard about Club Bahia. “I don’t drink, so it’s sort of challenging to find social activities that are stimulating and also get your endorphins going,” explains Kiely. “The line-dancing community is just wonderful—it’s not competitive, and you’re building something together. It can be almost spiritual, where you get a high just from dance.” For Munroe, who lives between L.A. and Toronto with her wife, taking part was unlike any other experience she’d had. “It’s pretty intersectional in terms of not just being a lesbian event, not just being a gay-guy event, not just being even a queer event—it’s really open to supportive allies [like Kiely] and open to [any] age,” she says.

Although communal line dancing has a long history—the first known instructions were recorded in a book of dance sheets dating back to the 1650s in England—its current form started to become popular in the U.S. during the late 1950s, and it has had a slow but steady ascent since then. What made Oil Can Harry’s, in particular, unique was that it was a safe, non-judgmental place for same-sex couples to line dance together and just be themselves. It wasn’t so much about the line dancing (which in itself was popular); rather, it was about the environment and how it transformed into more than just a bar for its patrons. That’s why Monaghan and Salisbury created Stud Country and why this event has been catching on with a new, younger generation who are seeking both a good time and an open-minded community.

“You don’t need to be great to do it. The fact that we can teach without being professional dancers speaks to the accessibility of it.”

Dallaire was so taken with the weekly dance events that he began searching for others and discovered the L.A. Wranglers, a non-profit queer line-dancing troupe that was started 22 years ago. He auditioned, got in and now travels around the U.S. and performs at various events, including the Stagecoach Festival, L.A. Pride and San Francisco’s Sundance Stompede. It’s a volunteer association that partners with other groups nationally and internationally—it’s even part of the same close- knit network as Club Bolo in Montreal, a line-dancing troupe in the Village neighbourhood that’s been around for 20 years.

Although the Wranglers’ skill level is new to Dallaire, line dancing was very much a part of his upbringing in Quebec’s Montérégie region. “When I was 10, my aunts would come pick me up every Monday and drive me to the town next to ours for line dancing,” he says. “It’s so funny that now I’m into it again but also that it’s the same routines from some of these old songs I learned 30 years ago.”

At the line-dancing evenings, there are usually two routines that are taught each night; then the floor opens up to let people do routines they’ve learned in the past. All the dances are designed to be paired with specific songs. “Most of the big dances that everyone loves come from [ just a few] choreographers,” says Dallaire. “There are websites where you can find all the spec sheets—you can look up the name of the song, and then you’ll find a sheet that [outlines] the dance.” Kiely also finds it helpful to look up YouTube videos in which the dances are performed step by step; it’s how he and Munroe learn a lot of the choreography they teach. To prepare, they spend hours rehearsing and memorizing the moves for each song. The choice of song and dance speed really depends on the club and the predominant age of the dancers. For example, the new generation of line-dancing nights, like Stud Country and Spurs, include more contemporary songs and are not limited to country music—there’s just as much Britney Spears as there is Brooks & Dunn—and the choreography is often faster. That’s why Dallaire, who now teaches at Stud Country once in a while, has started a new, slower-paced class. “I’m teaching a group of 70- to 80-year-old ladies in Beverly Hills at the Four Seasons Hotel,” he says with a laugh. “They love it. And so do I.”

When Kiely moved back home to Montreal this past summer, he reached out to Munroe, who was spending time in Toronto, to see if she would be interested in starting a line-dancing night at Champs with him. It was so successful that the pair tested it out in Toronto, and it has now found a home at the city’s Owls Club. It should be noted that, like Dallaire, Kiely and Munroe are not professional dancers; they just want to share the thrill, good vibes and open-minded atmosphere that these nights give to them.

There is, without a doubt, admiration in the crowd for those who nail the routines, but there are many people, like me, who just want to try it out—to move and have fun. “You don’t need to be great to do it,” reiterates Munroe. “The fact that we can teach without being professional dancers speaks to the accessibility of it. It’s not competitive; it’s also not performative. It’s communal—so much of it is about moving together.” Kiely agrees. “We forget how physical we are as human beings,” he says. “We forget what beautiful vessels we’re in and that we’re capable of so much.”

After my evening at Spurs—which I went into with absolutely no dance experience and no expectations—I completely understand why so many people get hooked on line dancing and why there’s such a strong desire to honour these spaces and spread the joy they bring. “I felt very moved by it almost immediately,” says Munroe. “Often at Bahia, I would be crying a little on the dance floor, just in awe of it all.”

Newsletter

Join our mailing list for the latest and biggest in fashion trends, beauty, culture and celebrity.

Read Next

Beauty

The Best Met Gala Beauty Looks Of All Time

From Taylor Swift's 'Bleachella' era to Rihanna's iconic 2011 braids, meet the best beauty moments in Met Gala history.

by : Katie Withington- Apr 26th, 2024

Culture

Benny Blanco Says He Fell in Love With Selena Gomez Without ‘Even Noticing’ It

Allow Benny Blanco to tell the straight-from-a-rom-com story of how he realized his feelings for his girlfriend and longtime friend.

by : Alyssa Bailey- Apr 26th, 2024

Culture

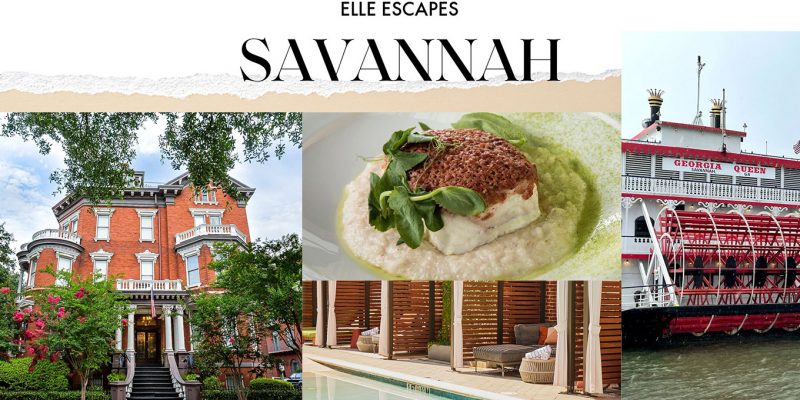

ELLE Escapes: Savannah

Where to go, stay, eat and drink in “the Hostess City of the South.”

by : ELLE- Apr 15th, 2024