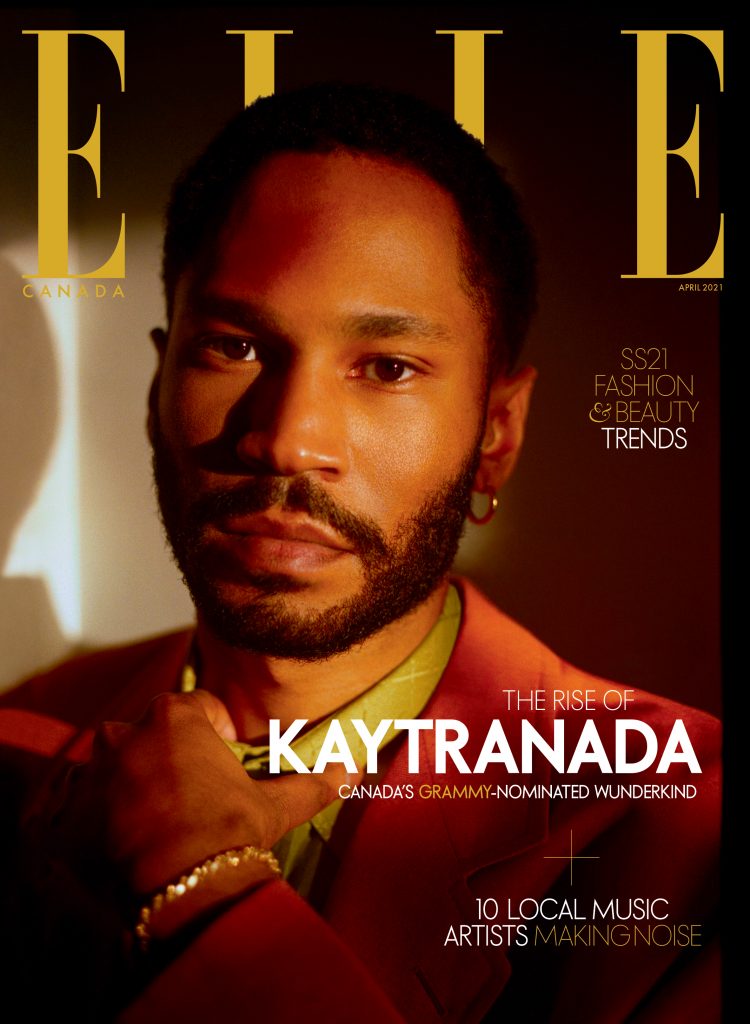

Culture

Kaytranada, Canada's Grammy-Winning Wunderkind

Haitian-born, Montreal-raised producer and DJ Kaytranada released one of the buzziest dance-music albums of 2020 — and never got to tour it. The 28-year-old talent opens up about his decade-long journey, his first three Grammy nods and what he yearns for most right now.

by : Kelsey Adams- Mar 11th, 2021

Xavier Tera

Imagine a room filled with a wound-up, tightly packed crowd of people, all waiting with bated breath. The air is charged with anticipation, and then, finally, there’s a momentous release as the first beat of the kick drum rushes the audience into a frenzy. Hips swing, arms float to the sky and inhibitions dissolve as the bass penetrates the undulating bodies. Everything is put out on the dance floor for a freedom that rivals a spiritual experience.

This is what it’s like to see Kaytranada perform live.

It’s been over a year since the tour for his latest album, Bubba, was abruptly cut short. The 17 tracks melt into one another like the hazy late hours in a club, when the adrenalin high is waning and people are just vibing together. His fans and friends are playing the album in their bedrooms, dancing to it alone and telling him that they’re craving that collective live-show moment. “People have been expressing that to me a lot, and I’m doing the same, honestly,” he says over Zoom from his apartment in Montreal. “You close your eyes, and just for a millisecond, you believe that you’re somewhere else.”

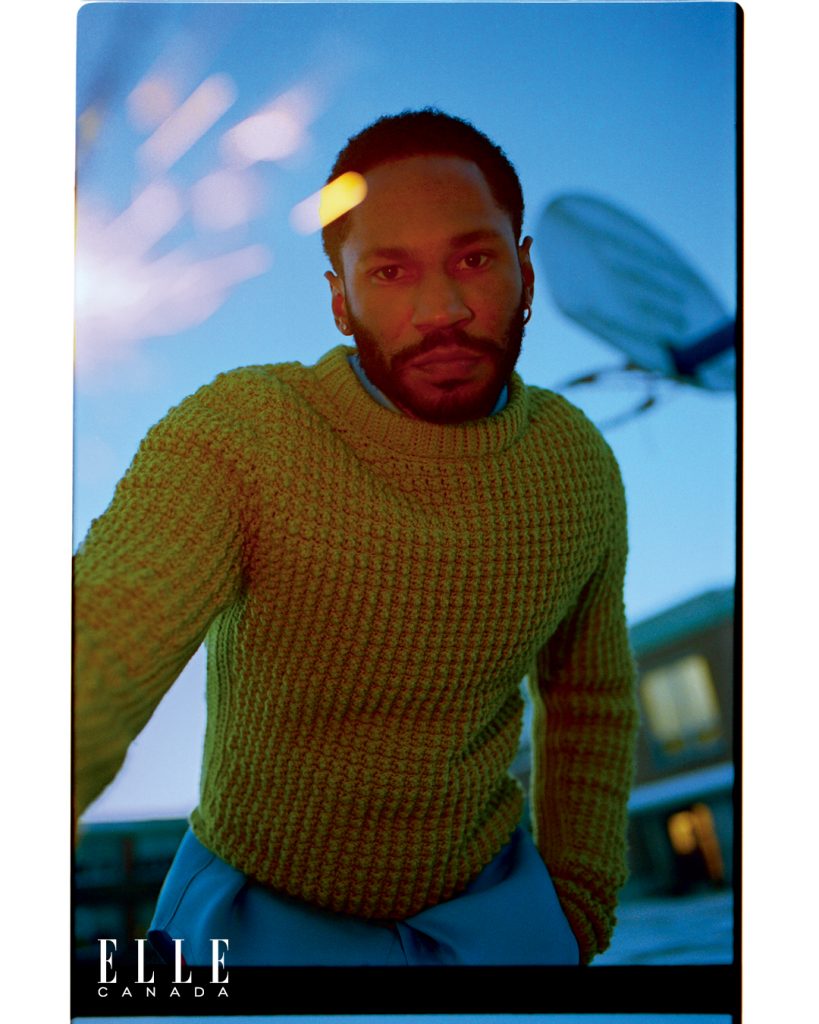

Xavier Tera

Xavier TeraSweater and shirt (Monthly Payment)

The evolution of Louis Kevin Celestin—from a teen making beats in his basement in the Montreal suburb of St. Hubert to the three-time Grammy-nominated artist and producer Kaytranada—was a decade-long journey. But he has always known how to tweak and play around with sonic expectations—how to push just far enough outside the box.

When Kaytranada (or “Kaytra”) emerged on the Montreal music scene in 2010 as Kaytradamus (a stage name he later dropped because of its similarity to Flosstradamus, another emerging producer), he was a kid experimenting with beat-making—seeing what he could create by sampling old vinyls and releasing remix after remix. “Back then, I was having way too much fun—messing around and just releasing whatever,” he says. He’s critical of some of his earlier work, like 2013’s Kaytra Todo EP, saying that there are tracks he now wishes he hadn’t included. That’s the downside of coming of age musically on the internet.

These days, a Kaytra production is instantly recognizable: There is the kick wave he uses in every beat; the mix of hip-hop, funk and house production styles he has melded together over time; and what he refers to as “that swing”—an undeniable element in all of his songs that makes them seem like they’re from the past, present and future all at the same time. There’s a whole crop of “how to make a Kaytranada-type beat” videos on YouTube—a surefire sign that you’ve made it as a producer in the digital age.

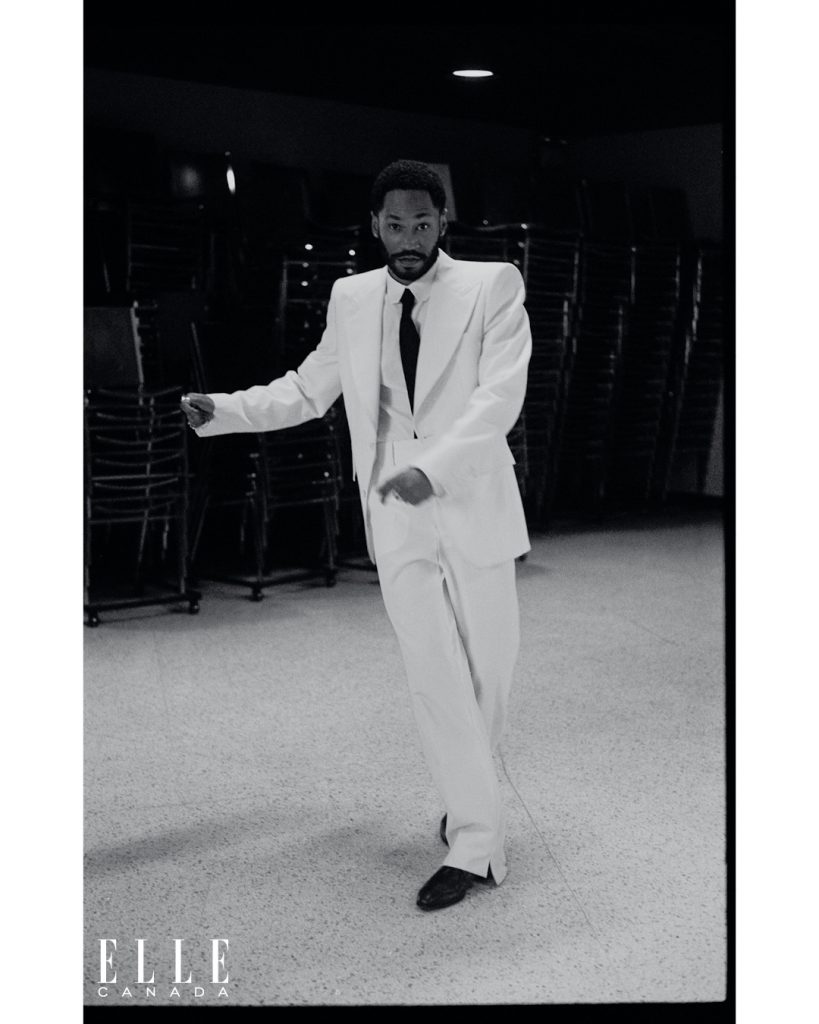

Xavier Tera

Xavier TeraSuit, shirt and tie (Louis Vuitton) and shoes (Kaytranada's own).

Kaytra is one of Canada’s freshest exports, but as a queer Black electronic artist, he’s also part of a larger narrative that defies definition—one he discovered over several years. Kaytra remembers really liking David Guetta, MSTRKRFT, Justice and artists under the Ed Banger Records label back in 2008, but at the time, he thought that what they were making was “white-people music.” He says that this disconnect from the history of electronic music was down to his ignorance about it at the time. “I thought something was wrong with me—like, ‘I’m one of those weird Black kids who love techno music.’”

His thinking was indicative of a bigger issue about the wilful erasure of Black and queer Black people’s contributions to the creation of these types of music: Thanks to the whitewashing of the legacies of house and techno, Black people have been disconnected from part of their music culture. However, there’s been a recent push to reclaim and proliferate the stories of innovators in this genre, like Frankie Knuckles, Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson. “It’s the same thing that happened with rap, rock, punk and so many music genres,” says Kaytra. “It happens a lot.”

The first time I saw Kaytranada live was at the Osheaga Music Festival in 2014. My friends and I trudged through mud and muscled our way to the very front of the stage. Although I’d been ravenously listening to everything he’d released, seeing him live was like a formal introduction, and the energy of his show was a sign of things to come. He was 22 and seemed shy but so in control. He brought out his parents and brother and did a meek little bow at the end, his reserved personality a balance to his larger-than-life set. Most of the world was introduced to Kaytranada in waves: His viral sets on Boiler Room (the British electronic-music livestream platform), his festival gigs across North America, Europe and Australia, his ubiquitous Janet Jackson “If” remix and his production credits on songs by some of today’s most innovative artists have all made him an international name.

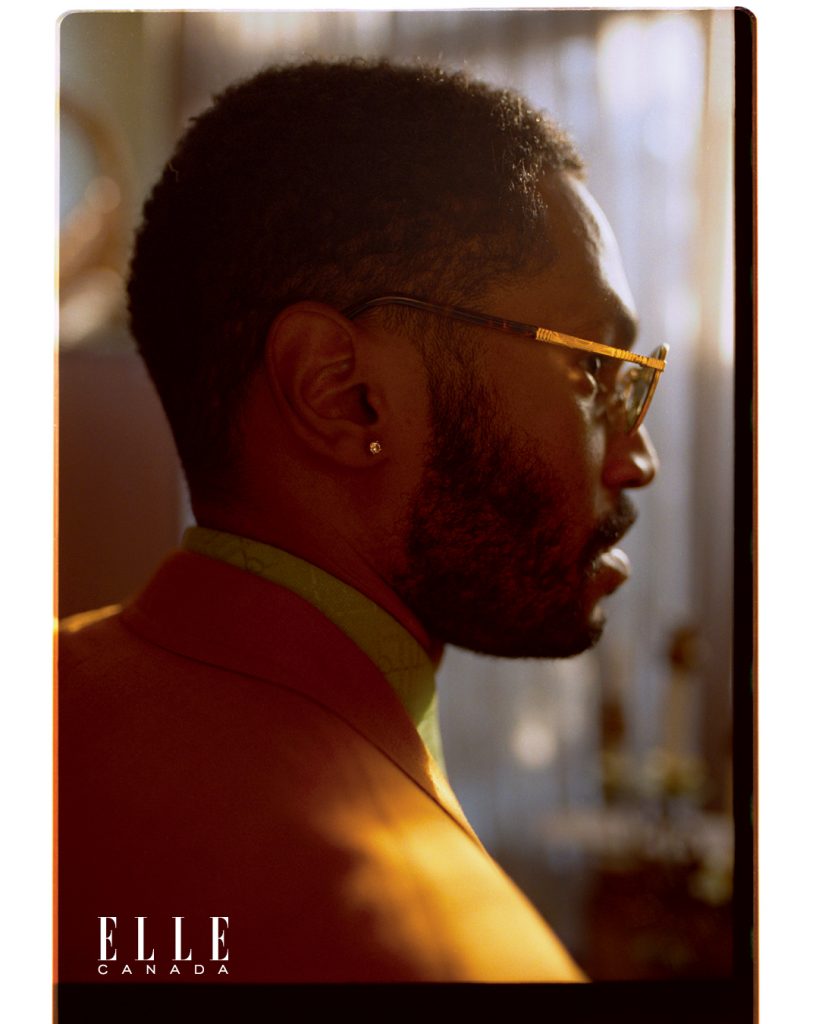

Xavier Tera

Xavier TeraBlazer and shirt (Gucci) and glasses and jewellery (Kaytranada's own).

After touring for years on the strength of his DJing, he hunkered down and completed his 2016 Polaris Music Prize-winning album, 99.9%. Its follow-up, Bubba, arrived at the end of 2019. It’s a dance-music album that didn’t get the amount of club play it deserved before the pandemic, despite featuring a whole roster of high-profile collaborators, including fellow Canadian Charlotte Day Wilson, Pharell Williams, Tinashe, SiR and Estelle. An entire world of Kaytranada production exists beyond his official studio releases: He has produced for Shay Lia (another Montrealer), Alicia Keys, Kali Uchis, Mick Jenkins, Goldlink, Vic Mensa, rapper Lou Phelps (Kaytra’s brother), The Internet, Chance the Rapper and Anderson Paak. (This isn’t even an exhaustive list.) Then there are his remixes, from the well known—Solange, Dua Lipa and Shawn Mendes—to the deep cuts—TLC and Missy Elliott.

Yet this year’s three Grammy nods have catapulted Kaytra into a new stratosphere of recognition. He was nominated in the Best New Artist, Best Dance/Electronic Album and Best Dance Recording categories and is thrilled that he’s being considered. He flits from genre to genre in his work but was intentional about making a dance-music album, so he’s happy about that validation. “I don’t make that music constantly,” he says. “But it’s just good to be recognized. It’s good for the music to be recognized in the right category.”

In January 2020, he was in discussion with Janet Jackson about working together on her forthcoming album. “It never went through,” he says. “She didn’t play games with COVID. She was talking about how it was going to take over the world.” And then it did. Like for all of us, Kaytra’s life was disrupted, and he returned from Los Angeles to Montreal for lockdown, his world tour postponed. One of the hardest parts of the first wave of isolation was that he was reeling from a recent breakup. “I’m surprised I made it through,” he says. “It has been so difficult. [It is] a moment [in which] you wish you had someone with you.”

Find the full story in the April issue of ELLE Canada — out on newsstands and on Apple News+ March 15th or read the digital issue. You can also subscribe for the latest in fashion, beauty and culture.

Xavier Tera

Xavier TeraPhotographer: Xavier Tera; stylist: Nariman Janghorban; creative director: Annie Horth; hair: MJ Deziel (Teamm/ Apart Studio); makeup: Nicolas Blanchet (Folio Montreal/ Pat McGrath Labs); editorial producer: Estelle Gervais; set coordinator: Laura Malisan; photography assistants: Ménad Kesraoui, Thibaut Ketterer and Mylène Castilloux; styling assistan: Manuela Bartolomeo.

Newsletter

Join our mailing list for the latest and biggest in fashion trends, beauty, culture and celebrity.

Read Next

Fashion

H&M's Latest Designer Collab With Rokh Just Dropped (And It's So Good)

We chatted with the emerging designer about the collaboration, his favourite pieces and more.

by : Melissa Fejtek- Apr 18th, 2024

Culture

5 Toronto Restaurants to Celebrate Mother’s Day

Treat your mom right with a meal at any of these amazing restaurants.

by : Rebecca Gao- Apr 18th, 2024

Culture

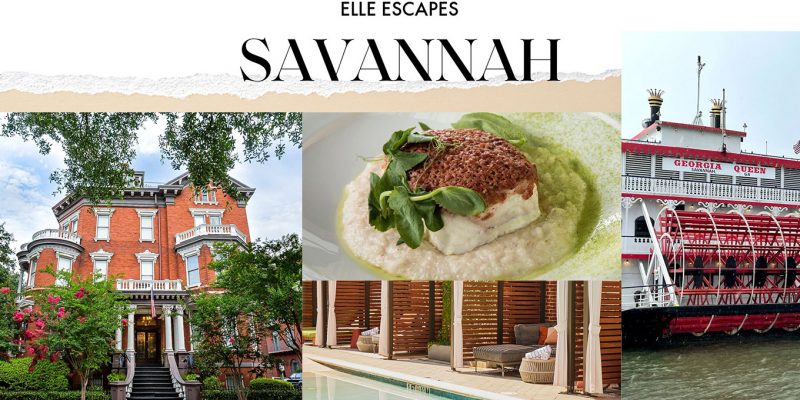

ELLE Escapes: Savannah

Where to go, stay, eat and drink in “the Hostess City of the South.”

by : ELLE- Apr 15th, 2024