Books

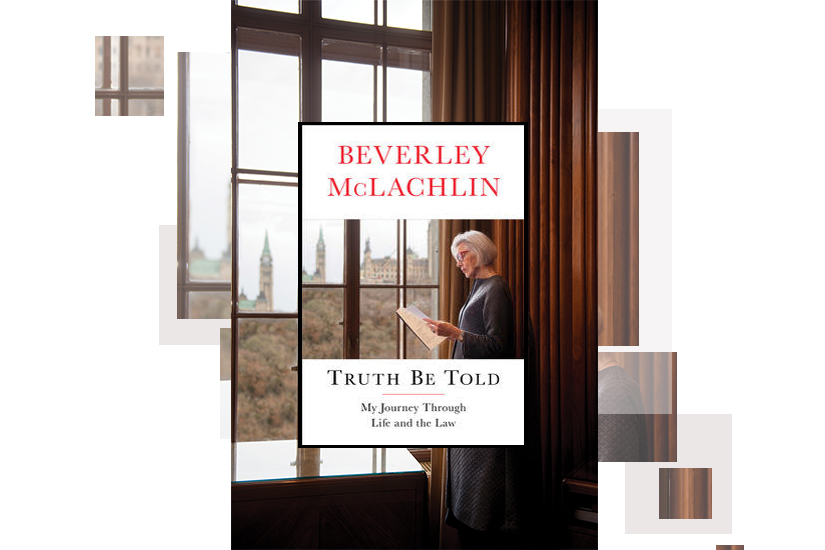

Meet Former Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin, the Powerful Voice Behind Some of Canada’s Biggest Issues

At a time when few women pursued law, McLachlin rose to the highest court in Canada and became our longest-serving chief justice.

by : ELLE Canada- Oct 18th, 2019

In partnership with

Beverley McLachlin’s memoir starts with ruminations on The Famous Five and the Persons Case, a remarkable moment in the fight for women’s rights in Canada and a great example of how the law must change as the world does. It’s certainly a concept that’s familiar to McLachlin, who is the longest-serving (2000 to 2017) chief justice in Canada and has presided over and rendered judgments on everything from assisted suicide to same-sex marriage (the latter of which she actually signed into law). It’s no surprise, then, that she decided to write a memoir and was able to shape an interesting story about her small-town beginnings, her law studies—often as the only woman in the room—and how she made her mark in her role as chief justice. If ever you needed a reminder that you can accomplish your dreams, this is it.

Why was setting the scene and unpacking the lessons of your childhood such an important part of the book?

“Well, this wasn’t just a book about my career. That would be a different book—very case-by-case, very jurisprudential. This is a memoir, and it’s about me. I was writing it about my life, and the only reason I wrote it is because others convinced me that I had had an exceptional and interesting life and that sharing it might help other people, particularly women, who might not think that that they have the background or advantages that would help them achieve whatever they want to do. So I decided to write a story about me and how I emerged from my small town and my childhood and went through life. And that’s the main point of the book. It’s one Canadian story.”

Throughout the book, you describe how some of the larger issues you presided over in your work ran parallel with your personal life. Did you find that this made an impact on your decisions?

“All judges have personal experiences—they’re human beings. The perspective they bring from their lives helps them to be better judges and helps them understand what problems people face and what the options are. I feel that those experiences, although some of them were difficult, didn’t shape one outcome or another, but they helped me understand what people like Sue Rodriguez*, for example, were asking. They helped me understand what her life was like. That kind of understanding—having encountered these things and dealt with them, whatever they may be—makes you a better judge.”

*Sue Rodriguez was an activist who was diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s disease and sought to end her own life, however, no doctor would help her. In 1993, her case went to the Supreme Court, which ultimately decided against her. (Although, for her part, McLachlin supported Rodriguez’s position.) Physician-assisted suicide would not be made legal until 2016, however, the case brought the conversation into the national discussion at the time.

Given the volume of cases you encountered, how did you decide what to include in the book?

“I tried to pick out some of the more important issues, the ones that touched me deeply. Of course, I could have gone on and on and on, but I chose cases that resonated with my personal values and cases that I may have struggled over. I tried to speak about issues more than particular cases.”

You mention a few times that you’ve always been a bit of a writer and that writing helped you work out issues. Did you find that to also be true with writing a memoir? Did it offer any clarity on your own story?

“It did. I started off thinking that I didn’t want to do it. I never thought I would write a memoir because, as one judge on the Supreme Court of Canada remarked, living once is enough. But I found this to be a very positive act. Going back and deliberately trying to think about how it was when you were a child and growing up and your parents and your siblings and your friends and putting it all together and going right up to the present—it helped me understand my life better and gave me a sense of coming home. If you’re at all inclined, whether or not you want to get published, it’s really satisfying to sit back and look over your life and write it down.”

When you were coming up as a young lawyer, did you understand the significance of being one of only a very few women—sometimes the only woman—pursuing that path?

“Oh, yes. I jokingly say I suffered from imposter syndrome almost all my life. As a woman going into law, which was dominated at that time by men, I always felt I was going into situations where I was in the minority or the only one. Very few women studied law, and even fewer went on to practice it. So the profession was very masculine. And women were, of course, allowed in, but you had to be really good, and you were watched very critically and people didn’t necessarily think you were going to succeed. The men were automatically entitled to succeed, and the women were sort of there in a ‘Well, let’s see how they do’ way. You felt very alone being the only woman in the room. And you had the feeling that everything that was said to you or anything you said was being judged through some sort of lens of gender. If you made a remark, then the question was always ‘Is she saying it as another lawyer or is she thinking that way because she’s a woman?’ I may have been wrong on occasion in thinking it, but you do see yourself as someone coming in from the outside and someone who’s a little different and someone who may have to do a little better to win the confidence of everyone and the men around you.”

Did you find that sort of pressure motivating or did you wish that it didn’t exist?

“Well, I didn’t really think about resenting it; I think it did motivate me to do my best. For a while, I was always feeling inadequate, and I realized at a certain point in my life, when I was feeling more confident, that this wasn’t something the men were feeling. I had developed this goal of always being perfect, and when I failed, I felt very badly about it. And then I got over it and realized that no one can be perfect—you just do your best job and then you move on. And it was a relief to me when I realized that.”

At what point in your life did that realization come to you?

“I think it was in the late ’70s and early ’80s, when I become a mother. And then when I went on the court, I realized I would just do the best I could instead of flagellating myself if something didn’t go the way I wanted it to.”

There’s a great anecdote in your book about a man who was in a courtroom full of women and said that he felt outnumbered—it was a great reversal of what you’re talking about here. Was that an important moment?

“It was a turning point early in my judging career. And it applies to diversity and everything else. It’s just a question of being able to put yourself in the shoes of another persona and being able to see from their perspective. When you do that, you say ‘Oh, yes, we really need diversity on the bench.’ It was an important teaching moment for me.”

What do you hope young women will get out of reading this?

“I hope they come out of it with a sense of confidence, that they can achieve what they want to achieve. I hope they also come out with a sense that they should do their very best in an honest way and that they should be resilient and persistent. I learned early in life that I really didn’t have the option to quit and do other things. There were times I questioned ‘Why am I doing this?’ I think some of that can be good. But often we throw in the towel too quickly on something that is really good for us. The law was really good for me, and even in the tough times, I learned to persist; I learned to be resilient, pick myself up and move on. Those are the lessons I hope are conveyed to other people.”

What was the biggest challenge in your role as chief justice?

“I didn’t have a clear idea of how to be a chief justice. I had two great chief justices before me, but I didn’t think I could be like either of them, so I decided that I would do as much as I could to help each judge on the court be as good a judge as they could be. And that sort of perspective, rather than a top-down perspective, was one I was comfortable with and one that helped me as chief justice. It meant that we were truly functioning as a group of equals, but because I was chief, I could do a little more in terms of administration and personal support to help judges do their work. And having approached it that way was, I think, exactly what suited my style, which is not a sort of top-down, decision-control model. It worked well, and for the most part, the court was happy and productive and served the country well. I don’t criticize those that came before—every person has their own style and every era has its own issues. I just tried to find a place where I was comfortable.”

You write about how it’s good for judgments to evolve as society changes. Can you talk a bit more about the evolution and interpretation of Canadian law?

“The constitution is a living treaty, capable of growth within its natural limits. That doesn’t mean it’s going to bolt all over the place, but it can put out new twigs and new leaves from time to time. That’s good because the law has to keep up with society as it changes. In the past few decades, our society has been changing immensely and at a very rapid rate, and it’s a real challenge for the law to keep up with that. More recently, we’ve had to deal with internet issues and social-media issues and mass-media issues, and those hadn’t been on the radar before. You take the old principles in good stead and apply them in a way that makes practical sense in today’s world.”

What do you wish more people knew about Canadian law?

“I think people should know how courts go about doing their business. I do try to describe in the book a little of what life was like on the court, the process. People sometimes have an idea that judges pull their judgments fully formed out of the air or that, somehow, they won’t be objective. Those are myths, really. I want people to understand how conscientious judges go about their work—how they try to understand and by an act of imagination put themselves in others’ positions, how they try to be very faithful to the evidence and facts and through all that, hopefully, come up with the best possible decision for a particular problem. I’d like people to understand there’s no magic in it—it’s a lot of hard work and it’s a lot of insistence on integrity and wisdom and trying to get it right that makes a person a good judge, and I think we have a lot of good judges on the Supreme Court of Canada.”

A moment that really touched me in the book was when you talked about encountering a same-sex married couple who thanked you for your role in making that possible. What was that like?

“You’re aware of it in an abstract way when you’re deciding cases of importance and of course you’re constantly preoccupied with that, but when you see the actual human beings who have been touched, it hits you in a different way. I have been deeply moved many times by people like that who came up to say ‘You changed my mother’s life’ or ‘You changed my life’ or ‘You made it possible for this to happen.’ I say ‘No, I didn’t, I was just doing my job; I was just writing a judgement,’ but they want to tell you how from their perspective you helped them. And I feel very humbled by that and very privileged that perhaps something I have done had a positive effect on society or helped people realize their dreams or helped them live their life the way they felt they ought to live it. It makes you feel very fortunate that you’ve had a career and a life where you’ve had a chance to do something for others.”

Newsletter

Join our mailing list for the latest and biggest in fashion trends, beauty, culture and celebrity.

Read Next

Fashion

These Will Be 2025’s Biggest Wedding Dress Trends

Dropped waists, bridal bows and bubble hemlines for the 2025 brides.

by : Lauren Knowles- Apr 16th, 2024

Fashion

16 Mother's Day Gifts for Every Type of Mom

From the loveliest spring fragrances to sentimental gifts she'll never stop loving.

by : Melissa Fejtek- Apr 16th, 2024

Beauty

Tested and Approved: A Skin Saviour That Works While You Sleep

Wake up with your glowiest skin yet—even if you didn’t clock eight hours.

by : ELLE Canada- Apr 11th, 2024