Fashion

Vivienne Westwood’s Impact Is More Important Than Ever

There’s something different about women designing for women, and with Westwood, her fierce defiance of societal norms was inherent in her designs.

by : Randi Bergman- Apr 9th, 2024

Getty Images

Dame Vivienne Westwood once said that the only possible effect one could have on the world was through unpopular ideas. You could say boundary pushing was the designer’s thing—from going commando when she collected her Order of the British Empire in 1992 to riding a tank to former British prime minister David Cameron’s house while protesting fracking in 2015 to protesting Brexit on her runway in 2018. Stunts aside, her unapologetic anti-fashion approach left an indelible mark. And just over a year after she left us, her ideas are more popular than ever.

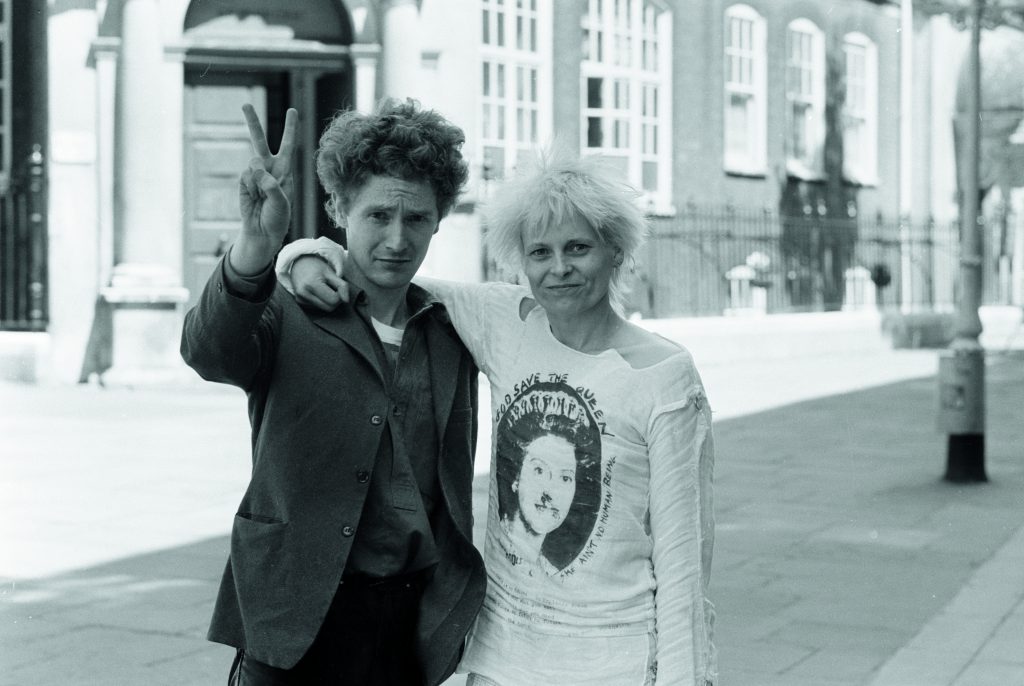

Westwood, who died in December 2022 at the age of 81, used traditional techniques and tailoring to push the limits of sexuality and politics in fashion over a 50-year career. She became known in the 1970s as one of the architects of the punk aesthetic, selling bondage, fetishwear and tattered vintage T-shirts out of her Sex boutique (later named “Seditionaries,” among other monikers). Her most famous tee was the “God Save the Queen” one—featuring a photo of Queen Elizabeth with a safety pin through her face—she created for the Sex Pistols. In the 1980s and ’90s, she entered the commercial sphere with her takes on historical garments, using tartan and tweed—then favoured by the conservative upper class—in sexed-up statement pieces and turning traditional Savile Row tailoring on its head with skewed silhouettes that flattered the body in a completely new way.

Getty

GettyIn the 2000s and beyond, she hit the mainstream with her sumptuous bridalwear (Carrie Bradshaw was famously left at the altar wearing one of Westwood’s gowns in the first Sex and the City movie) while at the same time railing against the excesses of the fashion industry through her work fighting climate change. “Buy less, choose well, make it last,” she often said. Even today, the Westwood brand operates as one of high fashion’s last independents, allowing it to avoid the pressures of conglomerates like LVMH and Kering, which have been known to ramp up the calendars and outputs of the fashion labels they own. By contrast, Westwood used her fashion shows partly as platforms to promote awareness of climate change. Her fall/winter 2019/2020 show, for example, featured models wearing anti-capitalist slogans like “We sold our soul for consumption.” She also launched Climate Revolution, a campaign to raise climate-change awareness.

In a way, doing all this as a woman was her most controversial act. In the year since Westwood’s earthly departure, much has been made about the dearth of women leading designer brands. A revolving door of fashion-house departures and appointments in 2023 included Sabato De Sarno becoming creative director at Gucci, Peter Hawkings taking the helm at Tom Ford and Seán McGirr replacing Sarah Burton at Alexander McQueen as well as several other high-profile appointments of white men. McGirr’s placement meant that all six of the fashion brands owned by Kering (including Balenciaga, Saint Laurent and Bottega Veneta) are led by a male.

There’s something different about women designing for women, and with Westwood, her fierce defiance of societal norms was inherent in her designs. Take her corsets, for example, which became a signature of the house after their debut in 1987 and redefined a garment that was historically oppressive for women as one that was as sexy as it was subversive. That same trait is apparent in the many female-identifying designers who see her as a guiding light, from fellow climate pioneer Stella McCartney to Michaela Stark, a London couturier whose lingerie is designed to expose parts of the body women are traditionally taught to hide. Stretch marks, saggy skin and uneven breasts take centre stage in Stark’s corsets, which defy the status quo. “Beauty is beauty, whether it’s conventional or unconventional, and I feel like fashion has suffocated so much of what beauty can be,” says Stark.

“Westwood had such a strong voice throughout her work, and that is so inspiring to designers like me because not only do you see a beautiful piece of clothing but you feel the punkness and the fight in it too.”

It seemed Westwood’s rebellious streak was alive and well when Stark’s designs were shown at the Victoria’s Secret fashion show last year—a complete one-eighty from the brand’s previous MO of showcasing lingerie on impossibly thin bodies. The collaboration received a backlash from those eager to maintain the status quo. “I knew it would ruffle feathers,” says Stark. “I know there’s no progress being made unless you scream it loudly and you scream it on a platform like Victoria’s Secret, which played such a big part in my own struggles with body dysmor- phia. It was a very empowering moment for me to disrupt this concept of the Angels in collaboration with [the brand].” Stark had the last laugh when, in a pure Westwood moment, she put one of the angry Instagram comments reacting to the collaboration—“Bring back Gisele,” a reference to 2000s Angel Gisele Bündchen—onto T-shirts sold on her website. “Westwood had such a strong voice throughout her work, and that is so inspiring to designers like me because not only do you see a beautiful piece of clothing but you feel the punkness and the fight in it too,” says Stark.

Westwood odes have popped up everywhere in the seasons since her passing. Marc Jacobs dedicated his spring/summer 2023 show—a parade of short-cropped peroxide-blond models in bustles, bustiers and platform boots akin to Westwood’s sky-high versions (so high, in fact, that Naomi Campbell once toppled over in them on the catwalk)—to the “godmother of punk.” At the time of Westwood’s passing, Jacobs posted a photo of her on Instagram as a young woman sporting the same peroxide spikes as his models. “I continue to learn from your words and all of your extraordinary creations,” he wrote in the caption. John Galliano’s tour de force spring/summer 2024 couture collection for Maison Margiela Artisanal, while featuring all the trappings of a quintessentially Galliano show, felt a little bit Westwood with its exaggerated corsets, sexily bizarro merkins and fundamental rejection of fashion’s present- day commerciality. Elsewhere, Westwood lives on in Chopova Lowena’s cult-fave DIY kilts, Charles Jeffrey’s so-called “drunk tailoring” via his streetwear brand, Loverboy, and countless Instagram posts devoted to documenting her legacy for a new generation. “When Vivienne’s career started, she was mocked and ridiculed by mainstream society for her designs and opinions. However, over time, many have been inspired by her and what she represents,” says Brianna Kennedy, a researcher who runs the Instagram account @thewestwoodarchives, a comprehensive library of Westwood’s work. “For a woman from a working-class background to become the fashion renegade she is today is inspiring on its own. I think it’s so important for women to have role models like Vivienne so they can see that it’s possible to change the world and do what you love, even if it feels impossible.”

Read more:

Newsletter

Join our mailing list for the latest and biggest in fashion trends, beauty, culture and celebrity.

Read Next

Decor

10 Amazon Decor Finds That Belong in a Designer’s Home

Yes, Amazon.

by : Maca Atencio- Apr 29th, 2024

Fashion

Pregnant Bellies Are Moving Into the Spotlight

Viva la MILF!

by : Jillian Vieira- Apr 29th, 2024

Beauty

Summer Prep: How to Feel Confident in Your Swimsuit

New Size-Inclusive Swimwear: Gillette Venus partners with The Saltwater Collective to Launch a Collection for Any Body

by : ELLE Canada- Apr 24th, 2024